When I was in college my friend Jim invited me to his home and introduced me to his aunt. Over a glass of scotch, “because it’s five o’clock somewhere,” she regaled us with her experiences as an engineer on the railroad during World War II, when women filled jobs previously held by men in order to help the war effort. I had never heard this description of the war—both of my parents served in the military. I was gratified to hear that women’s prospects had, at one time, been more exciting than mine were at that point. She concluded with a glib, “Of course, when the men came home we gave them back their jobs.”

This was in the days before the women’s movement had taken hold, but my sensitivities to my second-class status were already on the alert.

“THEIR jobs!” I screamed silently inside my head. “Their jobs! Why weren’t they YOUR jobs?”

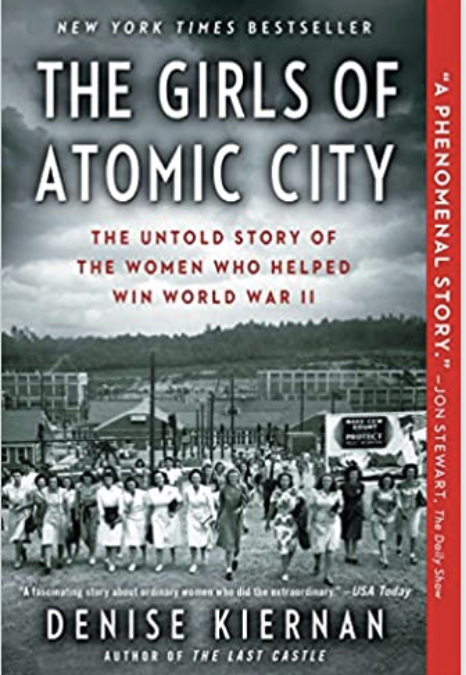

Being a proper Southerner I did not utter my challenge out loud, but that moment engraved itself on my consciousness: a revelation about women’s possibilities and further evidence of our unbalanced society. I was reminded of that event recently when I read Denise Kiernan’s The Girls of Atomic City, which relates the stories of women like Jim’s aunt who seized the opportunity and made their contributions to ending the war. The “girls” (and some of them were girls) of Atomic City moved to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, before Oak Ridge, Tennessee even existed. The stories of these women, as told by Kiernan, are also the history of the secretive community created to work on “The Product.”

The society at Oak Ridge reflected life in America at that time: It was segregated: black women like Kattie Strickland lived in quarters segregated from whites, left their children behind in Alabama to be raised by their grandmothers, and held menial jobs. It was social: the community provided an active social life with dances, bowling alleys, movies, and clubs. Some, like secretary Celia Szapka, leak pipe inspector Colleen Rosen, and statistician extraordinaire Jane Greer, met the men they would marry.

The society was also different from the rest of America: Women slogged through the mud to get to work, often carrying their shoes until they reached their workplace. They lived in a secret society, unable to speak about their work, even to others on “The Reservation.” Many of the women had jobs they would not have been offered on the outside, like Virginia Spivey, a chemist who analyzed “The Product,” guessing its content, but not its potential use. Like all those working at Oak Ridge, her position was so compartmentalized that she (and all the other women and men) did not know what “The Project” was until the bomb exploded over Japan.

This is a wonderfully written book, with personal stories, exalting the achievements of women without touting them, and discussing the science behind the project in understandable terms. It also demonstrates how women seized the opportunity when it was presented. I think Jim’s aunt would be tickled at women’s progress and would raise her martini glass in salute.