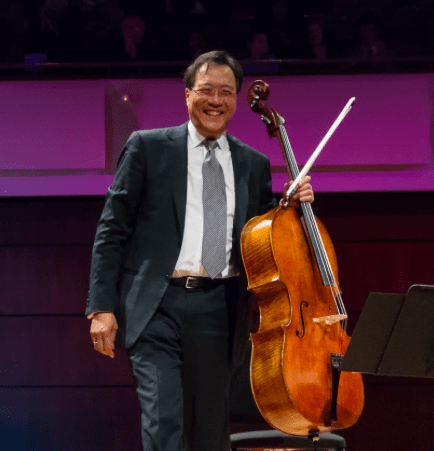

I was seated in the center of the auditorium, perfectly placed, due to the grace of a gracious benefactor. As the crowd poured into every available seat to hear Yo Yo Ma, the din of conversation remained reverential, a soft buzzing as in a holy place. When Yo Yo Ma entered the stage, the audience embraced him with their applause and he returned the embrace with his gracious bows and motions toward the audience. Like a good guest, he bowed and extended his arm toward the three abstract paintings of musical instruments on the backdrop, acknowledging the tasteful décor. Silently he had said, “You have made me feel welcome.”

The stage was bare except for a chair and the simple backdrop. Yo Yo Ma settled and began a simple, repetitive, partita by Turkish composer Ahmet Adnan Saygun. When the short piece ended, the cellist’s bow hung in the air over the cello, as if the vibrations from the instrument that we could no longer hear kept it airborne. No one breathed, respecting the musician’s artistic breath before applauding. But then the bow lowered to the strings and a vibrant unaccompanied Bach cello suite rumbled out from the belly of the cello and floated around and into the ears of those in the seats.

I was breathless and it took some time before I realized that the breathing of everyone else in the theater was also suspended. I have never been in a more silent audience. In a season ripe with colds, there were some quiet coughs during the evening but each time, the offender sounded almost embarrassed, muffling the body’s expression that was just as natural and explosive as the sound of Ma’s cello.

The applause arose from the hearts of the audience and extended down their arms into their hands. A communion of unspoken words. Yo Yo Ma patted his heart. There were no words, but we all heard them. “Your joy, your approval is what makes my heart beat.” He then applauded the audience and bowed, acknowledging reciprocal affection.

Ma then paired Mark O’Connor’s “Applachia Waltz” with another Bach suite. and finally he paired Chinese composer Zhao Jiping’s “Summer in the High Grassland” with a third Bach suite.

At the end of the concert, the audience stood in unison and demanded an encore. It has long puzzled me that audiences effectively says to a musician, “Gee, you played really well. You did your very best. So, now we demand more.” Good job, but it’s not enough? Ma closed with a Catalan folk song made famous by Pablo Casals, “Song of the Birds,” a song of freedom. At the end he once again touched his heart, applauded us, and made a special point to acknowledge the people in the balcony seats.

A reception for major donors followed the concert and we whizzed into the room with the special stickers on our lapels, provided by our benefactor. When Yo Yo Ma entered he acknowledged the skills of the musicians who were playing, high praise for a group of university students. His tribute to the accomplishments and importance of liberal arts education to our society was stirring. Then he spoke individually to each of the elderly ladies who waited to greet him. He held their hands in both of his, bowed to hear their words, as if the rest of the room had disappeared and they were the only person he wanted to engage. Finally he hugged each warmly.

I floated home, carried certainly on the notes still ringing in my head, but also buoyed by the grace and magnanimity of this artist. Yo Yo Ma embraces each person he meets, each audience he enthralls, each culture he visits. He combines the music and civilizations of the world.

It feels like a path for peace.